With fingers weary and worn,

With eyelids heavy and red,

A woman sat in unwomanly rags,

Plying her needle and thread—

Stitch! stitch! stitch!

In poverty, hunger, and dirt,

And still with a voice of dolorous pitch

She sang the “Song of the Shirt.”Thomas Hood

What “song” could the seamstress be singing? If we listen to it, what does it tell us about history, society, and people’s lives? What does it tell us about the greed of a few, leading to the destruction of the lives of many?

This poem, published by Thomas Hood in England in 1843, was written in honour of Mrs. Biddell, a seamstress forced to work under dreadful conditions and who had accrued a lot of debt to her employer. The poem became popular when it was published because it echoed the horrors faced by the working classes across England – poverty, hunger, poor living conditions, yet they were forced to work long hours for a measly amount.

182 years since the poem was published, The Song of the Shirt continues to echo truths about the garment industry, albeit the “poverty, hunger, and dirt” has changed its geographical location and its forms. When Thomas Hood was writing his poem, he did not know that the same scenes would repeat themselves in other places: in the garment factories of Dhaka, Bangladesh, for instance.

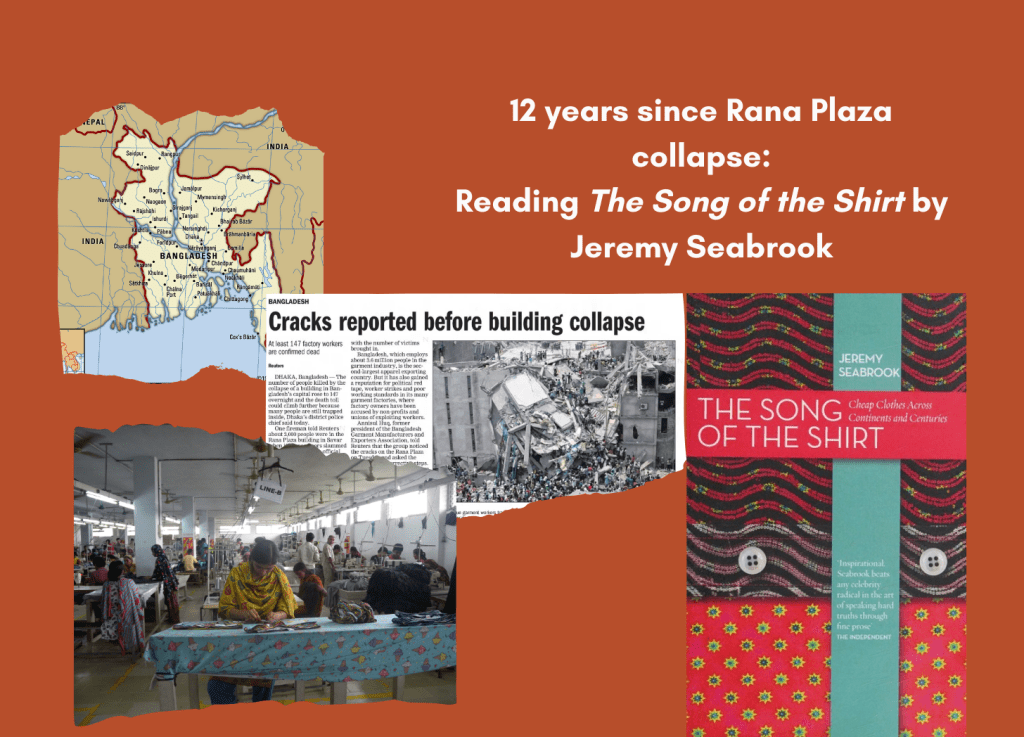

12 years ago, on 24 April 2013, the Rana Plaza disaster in Bangladesh shook the world of fashion and woke many of us up from the sleep that the hum of the endless machine of consumerism had lulled us into. The unfortunate collapse of a building in Dhaka housing several garment factories – in which 1,134 people died and about 2,500 were injured – demonstrated how abysmal the working standards are under which garment workers are working. One of the reasons the disaster was so shocking was that the building hosted factories of international well-known brands such as Benetton, Zara, Mango, Primark and Walmart.

Two years later, British author Jeremy Seabrook published his book The Song of the Shirt, borrowing its name from Thomas Hood’s poem, which takes us deeper into this issue, into the Bangladesh heartland and the history of garment production in the region of Bengal. A region divided after the Partition of India and Pakistan into the Indian state of West Bengal and until 1971, East Pakistan (now Bangladesh, after independence from Pakistan in 1971).

Seabrook’s book, in his words, “reflects on the mutability of progress.” It talks about how, unlike popular opinion, the formerly colonised regions were not a primitive, de-industrialised society. Rather, Bengal had a flourishing spinning and weaving industry, famous for its fine muslin cloths, which were wrapped in their own legends: that 30 yards of it could pass through a ring or fit into a matchbox. With the onset of colonialism, Bengal’s weaving industry was systematically destroyed by the British, who charged high tariffs for exporting Bengali cotton, kept the weavers in their debt, and imported cheap British cotton cloth to ensure that the cotton mills of Manchester and Lancashire profited and flourished. This is how Bengal, a prosperous, industrial region, was de-industrialised for the benefit of the British textile industry.

Now, in the 21st century, we have witnessed a resurgence of industrialisation in Bengal – especially in Bangladesh. Dhaka has become a major garment production hub. But the garment industry today in Dhaka is an ugly mirrored reflection of its colonial phase in history. Seabrook demonstrates that there is no want of oppression of young women’s labour in the industry, working and living a regimented life between the nearby slums and the factories. The factories are five or six storey high buildings, cramped with machines and their operatives. Space is so sparse, as Seabrook notes, that sometimes workers are sitting under machines to do their work. There are little to no safety standards in the garment factories, accidents like fires are common, and the workers are punished for any protest thanks to an ‘industrial police’ force whose aim is to quash dissent and protect the factory owners more than the workers.

So what makes young people – mainly women – come to work in these uncomfortable, unpleasant garment factories? Seabrook tells us that many of these young factory workers come in large numbers from the countryside to assist their families “wearied by floods and cyclones, by expenses for sickness, dowry or lost land.” The rivers take as much as they give: while the Meghna and Ganges rivers provide the people with fertile floodplains to grow rice, jute, or tea, but they are also “hungry, thieving rivers.” Families lose acres of fertile farmland, their homes, and all their means of survival to the strong river currents every year.

In this way, river erosion displaces swathes of people from the countryside to the city, looking for economic opportunities in the face of loss and hunger. They participate in the global economy and serve their “purpose in the fabrication of disposable apparel.” The global fashion industry and the demand for cheap clothes exploits migrant labour and takes advantage of the situation they are left in because of natural disasters and agrarian distress.

Abdul Samaat came as a child from Mehendiganj as a result of river erosion. The terrors of that time still live in his memory. “From July to September,” he says, “the current of the Meghna is very strong. Each year, you wonder whose land and life it will carry off. The river is an even greater thief than man.”

Jeremy Seabrook’s book paints a picture of Bangladesh that tells us the dark reality of fast fashion. He reflects on the deep connections between the age of imperialism and the current age of globalisation and capitalism; between Bengal and the industrial centers of England; between environmental destruction, migration and the exploitation of labour in the fashion industry. His book is a reminder, after all, that any discourse on fast fashion, the environment and the workers needs to center Bangladesh: that small delta country on whose back the global fashion empire is being built.

Leave a comment