We fancy that industry supports us, forgetting what supports industry

– Aldo Leopold, A Sand Country Almanac

Do we listen to our landscape? Have different words for all the clouds we see? Or live in a place long enough to be able to do the job of our weather apps?

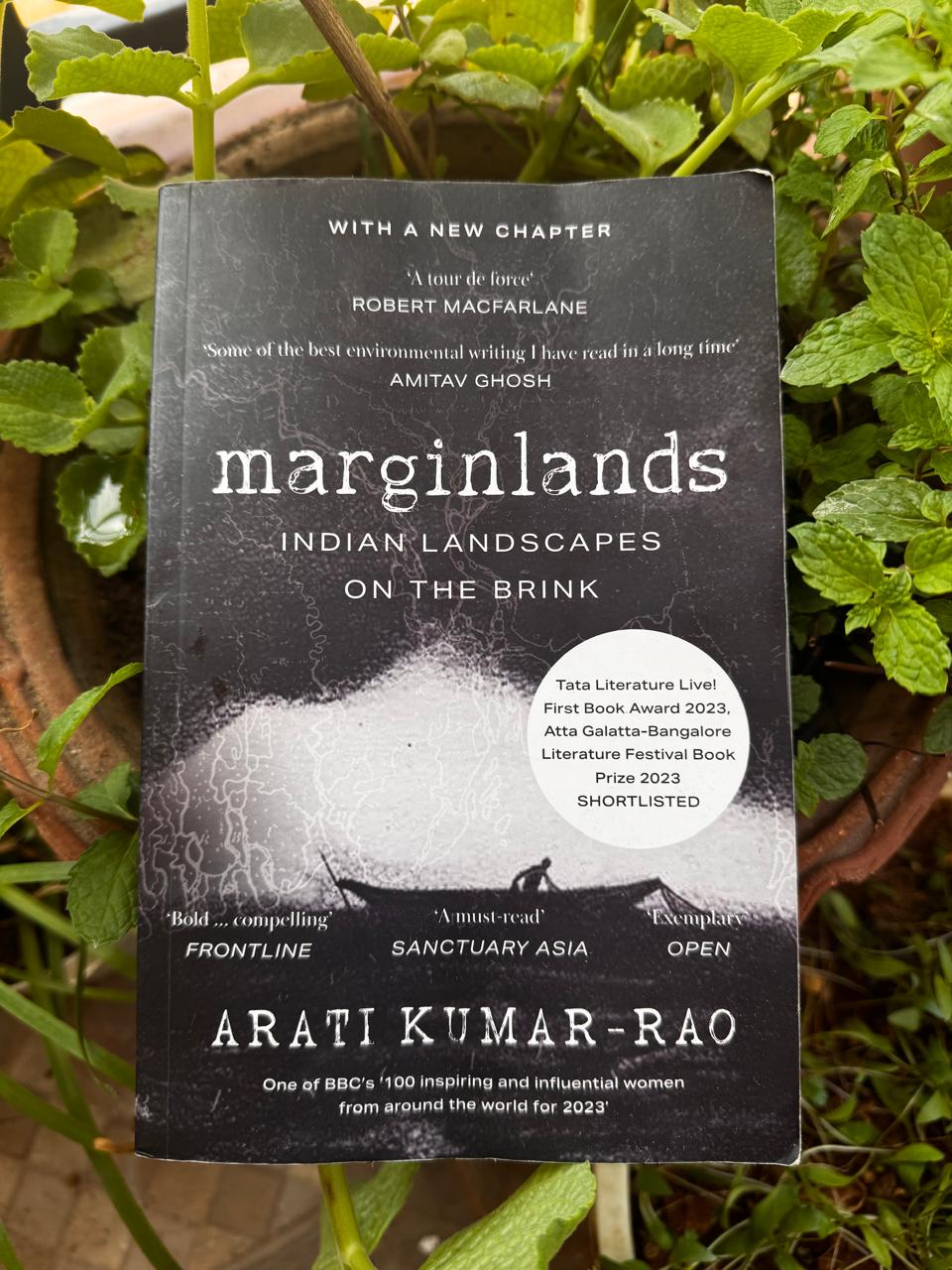

As someone living in a city, I have never thought much about whether or not I know my landscape, it’s merely a space in which I exist with my friends and family. I enjoy the freedom of the city, of being one in the thousands, earphones plugged in as I take the metro or auto to work, coming back and meeting friends, going out for brunch on Sundays and taking a walk in the park; that is as far as my landscape can stretch, it exists as I occupy it. Occupation does not mean knowledge however; at any moment, a city I have lived in for the past few years can become unfamiliar as I choose to leave it. That is the strangeness of our urban jungle, or at least what one could feel after reading Arati Kumar Rao’s Marginlands: Indian Landscapes on the Brink of Existence (I definitely did). A book that makes the reader think about the places we exist in sans earphones.

The book is exactly what it says it is – stories from the margins. Arati digs through the obvious and makes the reader glance into the landscapes tethered to the people, the animals, and the rest of the biodiversity who care for it across geographies. More importantly, she talks about how these relationships are changing.

Arati brings us narratives from different geographies; when she enters the desert and walks along with the locals, she opens her eyes to ‘villages planned around water’ and the communally constructed structures of water harvesting; she witnesses a human collaborate a fishing expedition with a wild animal (dolphins); environmentalists in Ladakh being inspired by the architecture of the Stupas and building huge water storage structures. Through these stories, we see the community and the land create a symbiotic relationship as slight shifts in seasons are anticipated and accordingly, preparations are made.

Knowing the land is knowing their past and predicting what comes next. Stories and myths play a key role in holding this knowledge and passing it down the generations. Every other landscape has myths that explain their existence, that are hyperlocal but also form part of a larger myth of the subcontinent. Like how mythology explains the origins of the Ganga, and in the Sundarbans, the people understand the boundaries occupied by humans and animals through stories of Bonbibi and Dokkhim Rai. The land not under the protection of Bonbibi is avoided.

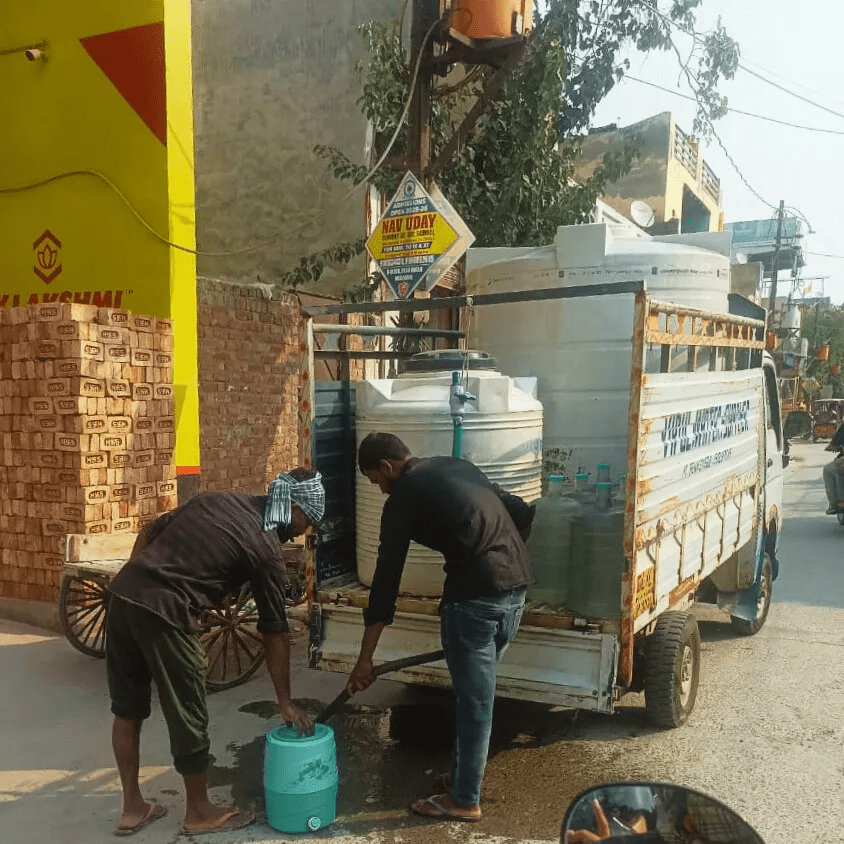

However, governmental interventions have often underestimated the knowledge of these communities as, she writes, “the lived language of the desert has been replaced with the universal, theoretical knowledge of nowhere in particular.” A particular instance from the book takes us to Jaisalmer, where 68% of land was deemed to be wasteland, without recognizing the water harvesting practices of the locals. When the government began opencast mining with single bench and deep hole blasting as a way to ‘better utilize’ this ‘wasteland’, it resulted in these ancient structures drying and depriving the local population of traditional sources of water.

More alarmingly, what she observes along with the communities living in these landscapes is that they have become unpredictable. She talks about Upper Assam, where a paddy farmer knows to look for the first sign of rain and that it takes 6 hours for a rain-fed river to reach the plains, the knowledge he learned from his father. Cut to 2015, when the Simen river flooded to the plain only an hour after the rain in the mountains. Boulders removed, river paths changes, the locals no longer can read their own land

Arati weaves her autobiography into the narrative by expressing her lifelong desire to be a storyteller and especially write on climate stories. Her observations from different landscapes always come back into a point of self-reflexivity, highlighting the deeply personal nature of environmental stories. Vivid descriptions that help us visualize the landscapes, even if we have never been to, and immerse us in it.

As we read Marginlands, we understand the importance of stories in connecting us with our landscapes. Yet, with the government interventions insensitive to this knowledge and landscapes transforming as a result, the relevance of such local knowledge is undermined and can no longer help people in their way of life. This becomes extremely crucial in the context of resilience towards impending climate change; how do you adapt without knowing what is changing?

This book is a call, therefore, for ‘seeing’. To experience the ecosystem in its whole, to understand and revere the place that each entity has, by themselves and through their relationships with us. To see the signs of rain without having to look into the weather app. It is a call, ultimately, to make ourselves less insular and one we must heed.

Leave a comment