Can Individual Actions Make Real Impact?

Sustainability is a buzzword we’re all familiar with. From corporations, governments , down to our own lifestyle choices. From carrying a cloth bag to the market to repurposing an old t-shirt as a cleaning cloth, sustainability as a concept seems ubiquitous, and rightly so. As climate change skeptics are gradually moving on from outright denial with “Climate Change is not real!” to claims like “It doesn’t matter, humans, fauna and flora are able to adapt!”; there is almost no doubt that we are heading towards a crisis. And with that, we’re all trying to do what we can to slow it down.

Yet, one question nags me occasionally, and I’m sure many of you can relate: Do our individual choices truly matter? Given that large corporations are responsible for the biggest share of emissions, there are times I think, “why am I forced to use a soggy paper straw when conglomerates are doing much worse and profiting from it, let alone going unpenalized.” It also doesn’t help knowing that the concept of “carbon footprint” is a push by Big Oil to shift the focus onto individual actions, diverting attention away from their massive contributions to climate change.

In a world where “sustainability practices” often feel like rhetoric more than reality, it’s natural to wonder if our personal actions can have any real impact. And to understand this, I tried to get what an individual CAN do in their power to manifest their idea of sustainability.

In this process, I turned to Albert Hirschman’s framework of Exit, Voice, and Loyalty. This classic framework, in its simplest form, explains different ways a consumer might react to a decline in the products, services, or even organizations one is associated with. Hirschman observed that people who find themselves dissatisfied with a product or a firm have a choice of three actions:

- Exit: Leave the product, company or any other engagement

- Voice: Express discontent with an intention to improve the situation

- Loyalty: Stay in that engagement with a hope that it will improve somehow

While this paper was published in 1970 and primarily addresses businesses and political institutions, its applications have been extended to other areas, including relationships, employment, and game theory. Some scholars have even added “Neglect,” where one consciously ignores the decline without taking any proactive step to counter it.

Let’s bring back our question: If corporations are largely responsible for our ailing planet, do our individual choices truly have the weight to shift corporate practices, or is it just another burden for consumers to bear? This is where Hirschman’s framework comes into play, helping us to see how different consumer actions shape sustainability, each of them presenting their own opportunities and limitations

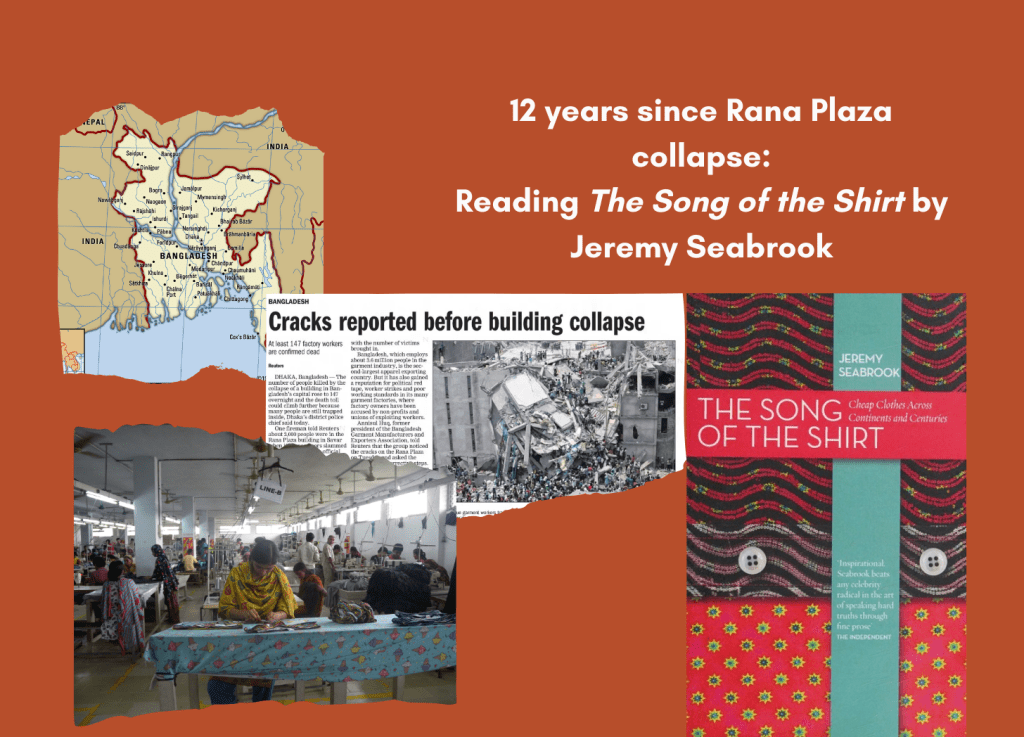

Exit is the simplest response, and the most common one: Just stop buying from unsustainable brands and opt for more eco-friendly alternatives. In the world of fast fashion, we’ve seen this trend with people opting out of brands like Shein, H&M, and Zara, after being criticized for exploitative labor practices and environmental degradation. Conscious customers are increasingly encouraging thrifting, or opting for more sustainable brands, effectively “exiting” from the fast fashion model of industry.

The impact of “Exit”, however, is not so clear cut. Several factors come into play. For instance, many sustainable alternatives are expensive or hard to find, making the ability to exit a privilege not everyone can afford. Also exit is most effective in competitive markets, where companies face pressure to retain customers. But in markets or where unsustainable practices are industry-wide, consumers often have limited alternatives.

This is where Voice becomes crucial.

Voice is where consumers advocate for change, raising public awareness and applying pressure on companies and governments to adopt sustainable practices. Movements like #WhoMadeMyClothes are prime examples, demanding transparency from brands and holding them accountable for their environmental and ethical practices.

The impact of voice is evident in cases like growing transparency in fashion brands’ supply chains or pressuring tech giants to set net-zero goals. Voice turns individual discontent into an industry-wide push for sustainability, and when driven by active civil society and activist groups, it can drive corporate accountability on a much larger scale than individual actions alone.

Finally, loyalty is when some customers remain loyal to brands they believe will eventually embrace sustainable practices, even if progress is slow. This is, however, a double-edged sword. While it gives companies time to get better, it can also enable complacency. If a loyal customer base is willing to tolerate slow progress, brands may have less incentive to accelerate change.

These actions don’t have to be mutually exclusive. Combining them can amplify impact. For example, when consumers both stop buying from fast-fashion brands (Exit) and publicly share why (Voice), it pushes brands to make meaningful changes to regain customer trust.

Now that we know theoretically that our individual and collective actions can influence business practices, this gives a perfect opportunity for businesses to frame sustainability as a “consumer choice” rather than a fundamental business responsibility.

However, at the risk of sounding cliche, I believe that the path to sustainability is ultimately about collective accountability. Hirschman’s Exit, Voice, and Loyalty are valuable tools for consumers to signal their values, but real progress requires businesses to respond with systemic change. They hold the resources and influence to make eco-friendly choices accessible and affordable, scaling their practices to a level that individuals alone could never achieve. Only when businesses, individuals, and collective voices align do we create a shared mission that transforms sustainability from a buzzword into action.

Leave a comment